Module 5: Open Research Software and Open Source

Introduction

Welcome to Module 5 of the Open Science MOOC: Open Research Software and Open Source. This module has been developed in the open through collaboration by an international team of Open Source afficianados. It comprises a series of videos, infographics, text-based reading (sorry), and practical tasks for you to sink you teeth into.

Don’t forget you can join in the discussions over at our open Slack channel. Please do introduce yourself, and tell us a bit about who you are, your background, and how you ended up here!

Who is this module for?

This module is designed primarily for computational researchers at the graduate and undergraduate level, as well as budding data scientists and any other researcher who uses analytical code or software. In a modern day research environment, this covers pretty much anyone who uses a computer.

“An article about computational result is advertising, not scholarship. The actual scholarship is the full software environment, code and data, that produced the result.” - J. Buckheit and D. L. Donoho, 1995.

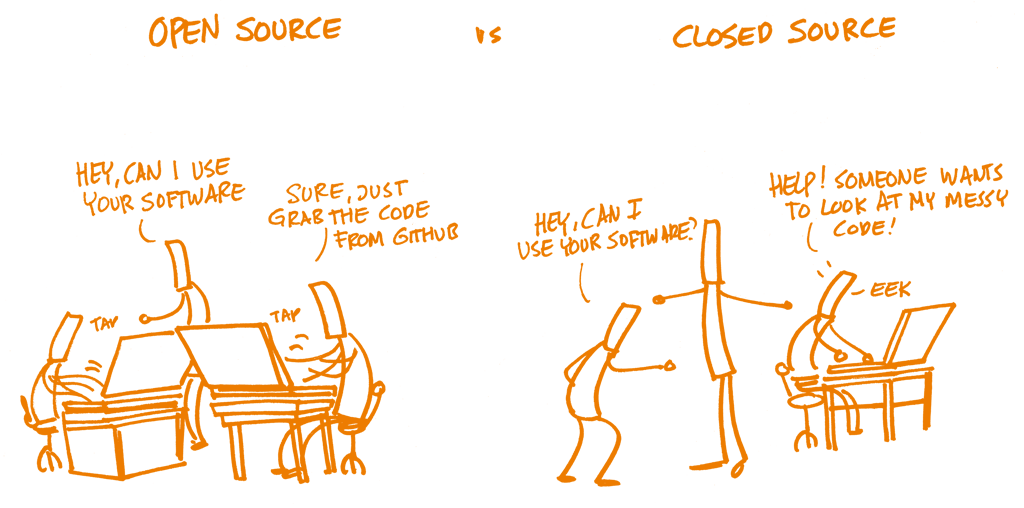

Software and technology underpin much of modern science, which is now almost inevitably computational in one way or another - search engines, social networking platforms, analytical software, digital publishing. With this, there is an ever-increasing demand for more sophisticated Open Source Software, matched by an increasing willingness for researchers to openly collaborate on new tools. The power of Open Source is in that it lowers the barriers to collaboration and adoption, therefore allowing ideas and technology to spread more rapidly. This Module will introduce the necessary tools required for transforming software into something that can be openly accessed and re-used by others.

Image by Patrick Hochstenbach (CC0 1.0 Universal)

Specific learning objectives for this Module:

-

Learn the characteristics of open software; understand the ethical, legal, economic, and research impact arguments for and against open software, and further understand the quality requirements of open code.

-

Be able to turn code made for personal use into open code which is accessible by others.

-

Use software (tools) that utilizes open content.

What is Open Source Software

Virtually all modern scientific research workflows rely on a range of software tools, either operating on different datasets, with different parameters, and applied iteratively in various ways (data science) or operating on different inputs and using models and methods to predict some output state (computational science). Open Source Software (OSS) is computer software in which the full source code is available under a specific license that enables other users to access, view, modify, and redistribute that code for any purpose. Because OSS requires such a license, it typically remains free of charge by default. This explicit licensing is also what differentiates OSS from free software. Re-using OSS for analysis, simulation and visualisation for research is also typically easier and more flexible compared to proprietary software.

OSS fits into the broader scheme of Open Science as it helps to make the full research environment, including the software that produced the research results, fully accessible. As such, it forms a necessary component for the best practices (Jiménez et al., 2018) and repeatability and reproducibility of research (both personally and by others), along with other components, such as sharing data (Stodden, 2010). In some cases, sharing of source code can even be conditional for the acceptance of associated research manuscripts (Shamir et al., 2013). It is also generally perceived to increase research impact (Vandwalle, 2012).

Some of common advantages for developers include:

- Increased developer loyalty and empowerment;

- Lower costs of services and marketing;

- Increased branding of services and products;

- Production of high quality software at lower expense;

- Flexibility and rapid innovation;

- Customisation and modular integration;

- Increased reliability and independence; and

- Based on open standards available to everyone.

As such, the main advantages for researchers (users) include lower costs, increased transparency, increased security and stability, no vendor ‘lock in’ with increased user control, and overall higher quality. Furthermore, sharing OSS allows researchers to receive credit for their efforts, for example through direct software citation (Smith et al., 2016).

Commonly used OSS include the Mozilla Firefox internet browser and the LibreOffice full office suite. LibreOffice is similar to the popular Microsoft Office, including a word processor, spreadsheet manager, and slide presentation software, but is completely free and Open Source.

Some regard the OSS movement to represent a counter-movement to neoliberalism and privatisation, through defiance of regulations and norms in the construction and re-use of information, and a potential transformation of modern-day capitalism through making software abundantly available with minimal effort. See The free/open source software movement: Resistance or change? by Panayiota Georgopoulou for more on this topic.

Principles of Open Source Software

The Open Source Initiative, one of the pioneers of OSS, offers the following definition:

-

Free Redistribution: The license shall not restrict any party from selling or giving away the software as a component of an aggregate software distribution containing programs from several different sources. The license shall not require a royalty or other fee for such sale.

-

Source Code: The program must include source code, and must allow distribution in source code as well as compiled form. Where some form of a product is not distributed with source code, there must be a well-publicized means of obtaining the source code for no more than a reasonable reproduction cost preferably, downloading via the Internet without charge. The source code must be the preferred form in which a programmer would modify the program. Deliberately obfuscated source code is not allowed. Intermediate forms such as the output of a preprocessor or translator are not allowed.

-

Derived Works: The license must allow modifications and derived works, and must allow them to be distributed under the same terms as the license of the original software.

-

Integrity of The Author’s Source Code: The license may restrict source-code from being distributed in modified form only if the license allows the distribution of “patch files” with the source code for the purpose of modifying the program at build time. The license must explicitly permit distribution of software built from modified source code. The license may require derived works to carry a different name or version number from the original software.

-

No Discrimination Against Persons or Groups: The license must not discriminate against any person or group of persons.

-

No Discrimination Against Fields of Endeavour: The license must not restrict anyone from making use of the program in a specific field of endeavour. For example, it may not restrict the program from being used in a business, or from being used for genetic research.

-

Distribution of License: The rights attached to the program must apply to all to whom the program is redistributed without the need for execution of an additional license by those parties.

-

License Must Not Be Specific to a Product: The rights attached to the program must not depend on the program’s being part of a particular software distribution. If the program is extracted from that distribution and used or distributed within the terms of the program’s license, all parties to whom the program is redistributed should have the same rights as those that are granted in conjunction with the original software distribution.

-

License Must Not Restrict Other Software: The license must not place restrictions on other software that is distributed along with the licensed software. For example, the license must not insist that all other programs distributed on the same medium must be open-source software.

-

License Must Be Technology-Neutral: No provision of the license may be predicated on any individual technology or style of interface.

Now, this all might be a little complex to remember. However, it can be summarised as making software as re-usable as possible for future works, while also being freely available. This principle of re-use is what separates OSS from ‘Free Software’. Free and Open Source Software (FOSS) is an inclusive term to describe software that can be classified as both free and Open Source. A good example of FOSS is the Ubuntu Linux operation system.

The big difference between free software and OSS is that the former must distribute updated versions under the same license as the original, whereas newer versions of OSS can be distributed under different licenses. FOSS combines the best of both worlds.

These definitions have now become widely adopted, both by international governments, as well as some large organisations such as the Mozilla Foundation and the Wikimedia Foundation.

An Open Source checklist

There are a number of existing platforms and tools that support OSS and collaboration. The Open Science Training Handbook provides a check-list to use for evaluating the ‘openness’ of existing research software, based on the Open Source Definition above:

- Is the software available to download and install?

- Can the software easily be installed on different platforms?

- Does the software have conditions on the use?

- Is the source code available for inspection?

- Is the full history of the source code available for inspection through a publicly available version history?

- Are the dependencies of the software (hardware and software) described properly? Do these dependencies require only a reasonably minimal amount of effort to obtain and use?

The Open Source community and its governance

There are two main camps within the free software community: The free software movement, and the OSS movement. Both have differing ideologies based on user liberties and the practical applications of software. Often, the term ‘FLOSS’ is used to reconcile these two political camps, and means ‘Free/Libre and Open Source Software’; Libre being French and Spanish for ‘free’ in the context of freedom.

Major organisations in the FLOSS space include the UK’s Software Sustainability Institute, who produce valuable resources such as their recent Software Deposit Guidance for Researchers.

For individual projects

Within OSS projects, there are typically three main formal roles:

- Maintainer;

- Contributor; and

- Committer.

A maintainer is a user with ‘commit’ access to implement suggested changes to the project. They have responsibility for the direction and improvement of the project. A contributor is someone who directly adds value to the project through issue resolution, code writing, or even external activities such as communications and event organisation. A committer is someone who can make ‘commits’ to the project (see Task 1).

Typically, roles are made public through either the README file, a Contributors file, or a separate team page for the project.

Existing platforms and tools for Open Source Software

Virtual environments and machines are becoming increasingly popular as high-powered research workflow enablers, and many of these are built upon OSS (e.g., operating systems, programming languages, and data processing frameworks). Popular services include Google Cloud and Amazon Web Services, which also assist with database storage and content delivery, as well as computational power. InsideDNA is a computing platform for reproducible research in bioinformatics, genomics and the life sciences.

As mentioned above, LibreOffice provides an Open Source alternative to Microsoft Office. The two are almost completely compatible, just with different default file formats. For citation managers, Zotero is the most popular Open Source alternative to proprietary platforms such as Mendeley or EndNote.

Zotero uses the BibTeX (pronounced ‘bib-tech’) format, based on LaTeX (pronounced ‘lay-tech’), and has browser plugins to make citation management simple. By integrating this with other software such as LibreOffice, it is now possible to have a fully Open Source research workflow in many cases.

GitHub

GitHub is a popular hosting site for both software and non-software content (often called ‘notebooks’), with added capabilities for version control, project management and tracking, and storage services. GitHub is built on top of the OSS Git, which enables users to work remotely to maintain, share, and collaborate on research software and other non-software based projects.

Version control is essentially a process that takes snapshots of the files in a repository, and tracks modifications to them. It records when the changes were made, what they were, and who did them. If several people are working on one file at once, any overlapping changes are detected, and must be resolved prior to continuing. This provides a much more streamlined and automated process than manually saving and recording changes as projects develop. It also avoids the inevitable lists of confusing named file versions…

For a lightning introduction to GitHub, including a simple working example, check the video below from GitHub On Demand (CC BY)!

Other similar project hosting services include BitBucket, GitLab, and Launchpad.